|

The world of Pi - V2.57 modif. 13/04/2013 |

|

|

|

Pi-Story or the history of the number Pi

Very short intro :

A more serious intro !

1

in the antiquity

in the antiquity

2 Ah finally a bit of analysis ! (18th century - end of 19th century)

3 The computer takes the computer

4 The BBP approach, yet more on

5 A quest with no end ?

References

Associated pages

- Mathematicians' pages (link on each of their names)

- Newton's algorithm

- Multiplication of two bigs integers by Fast Fourrier Transformation

- Finding the n-th digit of Pi without knowing the previous one (Plouffe's method)

- Record of the decimals of Pi throughout the centuries

Very short intro :

is a constant that finds it's origin from far antiquity.

What a journey travelled up till this day !

is a constant that finds it's origin from far antiquity.

What a journey travelled up till this day !

The history of the constant spreads over four

very distinct periods during which the spirits and the methods

associated to  were very differents. We remember basically :

were very differents. We remember basically :

1.  in the antiquity

in the antiquity

* Antiquity - 17th century : the geometric method of Archimedes triumphs

2. Ah, finally some analysis !

* 18th century - start of 20th century: it's a time where it rains discoveries and formulae constantly !

3. The computers take over work...

* 20th century : with the equations by Ramanujan and the computers, we can push at the calculus limits.

4. Let's take a walk in the decimals

* Nearing the millinium, Plouffe starts a revolution !

A more serious intro !

The number  occupies a particular place in the

mathematical world, and always constantly reaffirmed. It can boast to

have occupied the mathematicians mind since antiquity, and as Bergreen

and the Borwein brother [6], the calculation of

it's decimals is probably the only problem to have appeared since the

dawn of mathematics, and that is still current news in today's world.

However, the associated motivations have sensibly evolve throughout the

centuries.

occupies a particular place in the

mathematical world, and always constantly reaffirmed. It can boast to

have occupied the mathematicians mind since antiquity, and as Bergreen

and the Borwein brother [6], the calculation of

it's decimals is probably the only problem to have appeared since the

dawn of mathematics, and that is still current news in today's world.

However, the associated motivations have sensibly evolve throughout the

centuries.

First linked to the pratical and daily need of

the ancients, the evaluations always more precise of the number  then followed,

nearly like a game, some succesive discovery and fruitful analysis

formulae always more efficients from the renaisance until the 19th

century.

then followed,

nearly like a game, some succesive discovery and fruitful analysis

formulae always more efficients from the renaisance until the 19th

century.

The revolution of computers in the 20th

century will then completely change the game: the attraction of the

calculation did not come from the result itself, but from the method

of obtaining it, from a technical mathematical and algorithmitic point

of view. A new change of direction came since 1966, which tried to put

in relation the analytical expression of  and the profound

structure of its decimals. Of this exploration field at the frontier

of complexity theory was born a few still open conjecture on the

"random" nature of numerous mathematical constant (

and the profound

structure of its decimals. Of this exploration field at the frontier

of complexity theory was born a few still open conjecture on the

"random" nature of numerous mathematical constant ( ,

, , etc...).

Other consequence that till here was never guessed at, like the

possibility to obtain in certain bases the n-th digit without knowing

the previous one with little time or memory, we have renewed the

attraction of the calculation of digits or decimals of the number

, etc...).

Other consequence that till here was never guessed at, like the

possibility to obtain in certain bases the n-th digit without knowing

the previous one with little time or memory, we have renewed the

attraction of the calculation of digits or decimals of the number  .

.

This page offers to come back on those four

periods (Antiquity, 18th/19th century, 20th century, and since 1966) by

explaining the trails of thoughts and methods of calculations that lead

to knowing more than  decimals of

decimals of  at the start of

this third millenium ! We will achieve this essay by a little look the

actual motivation for the calculation of the decimals of

at the start of

this third millenium ! We will achieve this essay by a little look the

actual motivation for the calculation of the decimals of  .

.

1  in the antiquity

in the antiquity

With Pi, the time traveling machine is a

reality.... But of course, for more conformability, the modern and

usual language of mathematics are used here... Do not believe that the

Babylonians wrote the numbers in decimals. They didn't even know about

trigeonometry and used base 60 instead of base 10, in fraction

notation ( ). Firthermore,

the signs +, =,

). Firthermore,

the signs +, =, ,

, were only invented during the renaissance, the writtings

of the antiquity resembled more to a writting language than anything

else. The egyptians were a bit more advanced and used the decimal

system, manipulating fractions with a numerator of 1, and had invented

a sign + (two legs pointing left) and the - (two legs pointing right).

This being said, let us go back to the origins of the legend...

were only invented during the renaissance, the writtings

of the antiquity resembled more to a writting language than anything

else. The egyptians were a bit more advanced and used the decimal

system, manipulating fractions with a numerator of 1, and had invented

a sign + (two legs pointing left) and the - (two legs pointing right).

This being said, let us go back to the origins of the legend...

1.1

From the height of the pyramids,  looks down unto us !

looks down unto us !

I am sometimes asked in what year we discovered

! I

do not know the answer to this question because it's the result of a

long process. The ancients essentially needed it for the geometry and

measuring the surfaces of the earth, or in architecture, for example to

evaluate the height and the proportion of building. According to the

greek historian Herodote, we could find numerous geometrical relations

in the pyramids of Gizeh, to which he visited towards 450 BC

(that's more than 2000 years after their construction still!). For

example, a construction principle wanted that the aread of each lateral

surface is equal to the squared area of the side equal to the height of

the pyramid (which is accurate to roughly 99.3% for Kheops' pyramid!).

Numerous constants appear in this nearly magical way, since the ratio

of the height on the base of the pyramids with an error of 1,7% . This

remarquable coincidence are sometimes contested but are still

fascinating.

! I

do not know the answer to this question because it's the result of a

long process. The ancients essentially needed it for the geometry and

measuring the surfaces of the earth, or in architecture, for example to

evaluate the height and the proportion of building. According to the

greek historian Herodote, we could find numerous geometrical relations

in the pyramids of Gizeh, to which he visited towards 450 BC

(that's more than 2000 years after their construction still!). For

example, a construction principle wanted that the aread of each lateral

surface is equal to the squared area of the side equal to the height of

the pyramid (which is accurate to roughly 99.3% for Kheops' pyramid!).

Numerous constants appear in this nearly magical way, since the ratio

of the height on the base of the pyramids with an error of 1,7% . This

remarquable coincidence are sometimes contested but are still

fascinating.

The most ancient object where  intervenes more

or less implicitely is a babylonian tablette in cuniform writting,

discovered in 1936 and which goes back to the period 1900-1600 B.C. It

evaluated the perimeter of an hexagon to

intervenes more

or less implicitely is a babylonian tablette in cuniform writting,

discovered in 1936 and which goes back to the period 1900-1600 B.C. It

evaluated the perimeter of an hexagon to  times the

one of a circonscibed circle (either

times the

one of a circonscibed circle (either ![[0,57,36]](../histoire/histoire24x.gif) in

their base

in

their base  from which we have seconds/minutes left), which comes down to

estimating

from which we have seconds/minutes left), which comes down to

estimating  . It's officially the

oldest approximation known of

. It's officially the

oldest approximation known of  !

!

Similarly, to come back to egyptians, the

famous papyrus of Rhind written in hieratic writting and discovered in

1855 by A. H. Rhind at Louxor relating a serie of ancients problems

recopied by the scribed Ahmes. The number affirm that

the area of a disc of diameter

affirm that

the area of a disc of diameter  is equal to 64 , or the square of the diameter

to which we removed

is equal to 64 , or the square of the diameter

to which we removed  of it's length

of it's length  . This comes down to estimating

. This comes down to estimating  . They

probably came to this idea by aproximating the area of this disk by the

one of an octagon partition in squares and triangles of side 1,

and which then gives an area of 63 (probleme number

. They

probably came to this idea by aproximating the area of this disk by the

one of an octagon partition in squares and triangles of side 1,

and which then gives an area of 63 (probleme number  48). Note that

the Egyptians only work with fractions with the form

48). Note that

the Egyptians only work with fractions with the form  and that they

had opted for the best approximation of this kind this the diminution

of

and that they

had opted for the best approximation of this kind this the diminution

of  is

better than the diminition of

is

better than the diminition of  . Notice anyway (let us be fair!) that those

rudimentary tools furnished some value with errors of less than 1%.

This same kind of method will be applied in India (600 B.C) or in China

(150 A.D.)

. Notice anyway (let us be fair!) that those

rudimentary tools furnished some value with errors of less than 1%.

This same kind of method will be applied in India (600 B.C) or in China

(150 A.D.)

In the antiquity, we visibly quickly notices that the ratio between the parameter of a circle and it's diameter was a constant. Furthermore we know that the Egyptians had understood that the ratio linked to the perimeter of a circle and the one link to it's area was the same.

|

|

|

| Rhind's papyrus conserved at the British Museum (1800-1650 B.C.) |

|

|

| |

We don't know if this was the case for the

Babylonians, or even if those civilisation were conscious of having

obtained a rought value of  . We need to note that the diffusion of

knoledge at that era was rather reduced, and numerous other

approximation, sometime rather bad one did spring up after the

discovery of those first value. Hence, after the Egyptians and the

Babylonians, it's a bit empty... The Chinesse towards -1200 gives 3 as

a value, this shows a certain lack of research on the subjects! The

Bible, lacking a bit of divine inspiration for the occasion, also gives

3 as a value for

. We need to note that the diffusion of

knoledge at that era was rather reduced, and numerous other

approximation, sometime rather bad one did spring up after the

discovery of those first value. Hence, after the Egyptians and the

Babylonians, it's a bit empty... The Chinesse towards -1200 gives 3 as

a value, this shows a certain lack of research on the subjects! The

Bible, lacking a bit of divine inspiration for the occasion, also gives

3 as a value for  towards -550 B.C... The passage on the founder Hiram and

his chauldron stayed famous, here is the quote "He made the Sea of cast

metal, circular in shape, measuring ten cubits from rim to rim and five

cubits high. It took a line of thirty cubits to measure around it".

30/10=3, no mistakes. We will say a lot later that the quote concerned

the inside contour of the chouldron to calm the debate, but the absence

of precision since founders don't need it seems the oly

justification... Luckly, here are the Greeks that will put a bit of

order in all of this...

towards -550 B.C... The passage on the founder Hiram and

his chauldron stayed famous, here is the quote "He made the Sea of cast

metal, circular in shape, measuring ten cubits from rim to rim and five

cubits high. It took a line of thirty cubits to measure around it".

30/10=3, no mistakes. We will say a lot later that the quote concerned

the inside contour of the chouldron to calm the debate, but the absence

of precision since founders don't need it seems the oly

justification... Luckly, here are the Greeks that will put a bit of

order in all of this...

1.2 Eureka !! : The exhaustion principle with the greeks

The greek mathematicians were often considered as the first to really worry about proofs. The problems that preoccupied them stayed however mainly geometrical. Among them, the problem to build a square of the same area as a circle (the famous squaring a circle) was initiated, at least historicaly, by Anaxagore of Clazomène (500-428 B.C.) during a stay in prison for heriticity (he dared state in particular that the moon only reflected the light of the sun! It was no joking matter back then !). If numerous solution were then proposed, the problem became unsolvable for 23 century when Euclide added the conditions that it could solved uniquely :

- of an unmarque straight edge and a compas,

- in a finite number of stages (implicitely).

The link between those condition and the algebraic properties of numbers that flow from it was properly stated only in 1837 by Pierre Laurent Wantzel :

Theorem 1.1 Numbers finitely defined with the help of the ruler and compas are of size that can be defined by simple algebraic operations (additions, multiplications, extractions of roots....) in other words roots.

Even if numbers defined by radicals are

algebraic (roots of polynomials with coefficients in  ),

Abel proved in 1824 that not all algebraic numbers can always be

expressed by radicals as soon as the degree of the polynomial reached

5, and Liouville showed in 1851 the existence of non algebraic numbers,

i.e. transcendental. The problem of squaring the circle came quickly

down in the middle of the 19th century to the problem of the

transcendence of

),

Abel proved in 1824 that not all algebraic numbers can always be

expressed by radicals as soon as the degree of the polynomial reached

5, and Liouville showed in 1851 the existence of non algebraic numbers,

i.e. transcendental. The problem of squaring the circle came quickly

down in the middle of the 19th century to the problem of the

transcendence of  .

.

The distance which seperated the greek

geometric conception and the formal expression of squaring the circle

problem explained the slow growing of the mathematicians toward the

final and rigourous proof of the transcendence of  in 1882 by Lindemann , which would nail this old

debated old of more than 23 centuries !

in 1882 by Lindemann , which would nail this old

debated old of more than 23 centuries !

With the tools that the greek had, the solution proposed for the squaring the circle called most of the time for an infinite number of steps like the quadratic of Dinostrate, constructed initially by Hippias d’Elis towards 430 B.C. or even the exhaustion method.

This last one was generally attributed to

Antiphon ( 430

avant J.C.) or Eudoxe of Cnide (408-355 B.C.), and consist of

constructing a polygon whose number of sides will increase until it

became very like a circle.This brilliant idea hit the problem of a lack

of notion of limits in that era. We now know that it's not because a

property is true for all integer  that it is true at the limit (

that it is true at the limit ( ). In

other words, even if a polygon of side

). In

other words, even if a polygon of side  is squarable,

this does not mean that it's limit - the circle - is also,

contrary to Antiphon's idea. The brilliant Euclide (330-275 B.C.) write

nevertheless that by considering a polygon with a great numbers of

sides, we can "make the difference between the area to calculate and

the area of the polygon that have constructed smaller than any positive

quantity pre-assigned, no matter how small" (according to [12]), which is a

conception suprisingly close to the formalisation of limits in

mathematics of the 19th century. He deduce from it that the area of the

circle was proportional to the square of its diameter (Elements 12.2)

is squarable,

this does not mean that it's limit - the circle - is also,

contrary to Antiphon's idea. The brilliant Euclide (330-275 B.C.) write

nevertheless that by considering a polygon with a great numbers of

sides, we can "make the difference between the area to calculate and

the area of the polygon that have constructed smaller than any positive

quantity pre-assigned, no matter how small" (according to [12]), which is a

conception suprisingly close to the formalisation of limits in

mathematics of the 19th century. He deduce from it that the area of the

circle was proportional to the square of its diameter (Elements 12.2)

|

|

|

| Two pages from Euclide's Elements |

|

|

| |

|

|

|

| Euclide (365-300 B.C.) |

|

|

| |

We need to wait however for Archimedes

(287-212 B.C.) and his paper “On the measure of the circle” for this

idea to be efficiently applied to the evaluation of  . The first of

these 3 theorems states that the ratio of the area of a disk to the

square of its radius is equal to the ratio of its perimeter to its

diameter. The third problem explicitely states that

. The first of

these 3 theorems states that the ratio of the area of a disk to the

square of its radius is equal to the ratio of its perimeter to its

diameter. The third problem explicitely states that

|

|

|

| Archimedes (287-212 B.C.) |

|

|

| |

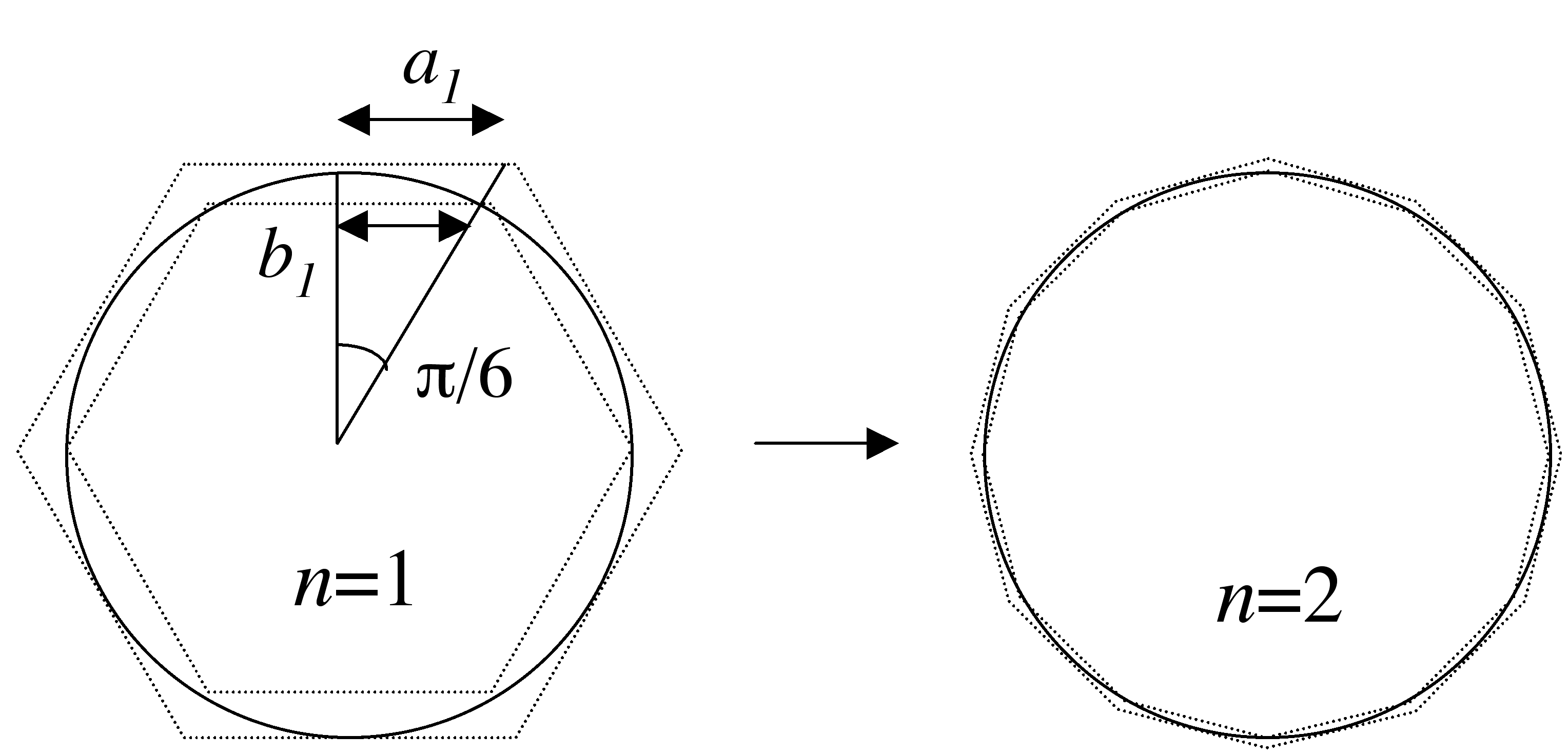

Let us take the exhaustion principle, it

exhibites a formal relation between a polygon of  sides with one

of

sides with one

of  sides

(see Archimedes's page).

Starting from two hexagons respectively inscribed and circonscribed, he

obtained the approximation 1

with two polygons of 96 sided ! This amazing calculation was made with

no algebraic notation, coherant numeration (the greeks used an additive

numerations like the romains), nor the knowledge of trigonometrie, and

with only Euclide's geometry. He formalised it as follow: Let

sides

(see Archimedes's page).

Starting from two hexagons respectively inscribed and circonscribed, he

obtained the approximation 1

with two polygons of 96 sided ! This amazing calculation was made with

no algebraic notation, coherant numeration (the greeks used an additive

numerations like the romains), nor the knowledge of trigonometrie, and

with only Euclide's geometry. He formalised it as follow: Let  and

and  be the semi

perimeters of polygons of

be the semi

perimeters of polygons of  sided respectively circonscribed and

inscribed in a circle of radius 1. The hexagon gives

sided respectively circonscribed and

inscribed in a circle of radius 1. The hexagon gives  and

and  . We then

have the recurrance formulae

. We then

have the recurrance formulae

|

(2) |

which gives  .

Archimedes pushed his calculations up to

.

Archimedes pushed his calculations up to  . The case

. The case  and

and  are

illustrated in the picture below.

are

illustrated in the picture below.

|

|

|

and and  of Archimedes' iteration of Archimedes' iteration |

|

|

| |

The proof of the convergence and the adjacence

of the two sequence is straight forward if we note that  and

and  . We hence

obtain

. We hence

obtain

|

(3) |

which assures a number of correct decimals equal

to  iterations roughly (3 decimals in 5 stages). We will qualify this

convergence to be linear. The brilliance of Archimedes

was already well know in that era, that

Tropfke [25] said

that the value

iterations roughly (3 decimals in 5 stages). We will qualify this

convergence to be linear. The brilliance of Archimedes

was already well know in that era, that

Tropfke [25] said

that the value  quickly replaced in Alexandria

the old value

quickly replaced in Alexandria

the old value  =

= , of more easy use but a lot less precise, and that it

was spread till India and even in China in the 5th century.

Ptolémée improved a bit the result using trigonometric

tables

, of more easy use but a lot less precise, and that it

was spread till India and even in China in the 5th century.

Ptolémée improved a bit the result using trigonometric

tables

1.3 Traveling...

After Archimedes, the mathematician night fall on the East for 1500 years.... It is true that the numerical system of the romains for example is of not much use for calculation (try to multiply LVIII by XCVI !) and they did not leave much behind them in tems of mathematical works. But things happens else where. Even if the asian, arabian or indian mathematicians just applied the same method of Archimedes, or a slight variant for 20 century, they offer better and better approximation. Hence, in India, we also work since Aryabhata offers, towards 500 B.C., 3 exact decimals. But, it was in China where the decimal system was always used, that the progress was faster. Tsu Chung Chih seems to be the first to give the famous fraction 355/113 = 3,14159292... towards 480 A.D. i.e. 6 decimals. The Arabians and Persians are not left behind since in their Hexadecimal, Al Kashi calculated with virtuosity 10 digits i.e. 14 decimals in 1949.... Absolute record !

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Aryabhata (476-550) | Tsu Chung-Chi (430-501) | Al-Kashi (1390-1450) |

|

|

|

|

| |

But the decimal notation starts to slowly

impose itself in Europe in the Middle ages and it all natural that the

West wakes up: it's Fibonacci, one of the

few great mathematician of the era and knowledgable in decimal

notation, which illustarate first of all and get  =3,1418...

meah...

=3,1418...

meah...

|

|

|

| Fibonacci (1175-1250) |

|

|

| |

Note that we did not yet understand precisely the transcendant nature of Pi (which is quite normal...) since Nicolas de Cues said in the 15th century

Regiomontanus will prove (!) that this value is wrong... Nicolas de Cues used a varient of the method by Archimède.  |

|

|

| Nicolas de Cues (1401-1464) |

|

|

| |

From time to time, a few try to be original.

Hence, Descartes

(1596-1650) took the problem the other way and offered his method of

isoperimeters which does not involve the perimeter of polygons but the

diameter of those polygons, whose perimeter is fixed. Viete also derived a first infinite product in

1593 (without proving it, but well, it wasn't usual to in that time!)

by looking at the area and not the perimeter:

|

(5) |

But the convergence is so slow that he still prefered to use Archimède's method to calculate himself 9 decimals in 1593.

|

|

|

|

|

| René Descartes (1596-1650) | Viete (1540-1603) |

|

|

|

| |

With simple 1000 years behind on the Chinese

and Tsu Chung Chih, but it is his name who was remembered,

Adrian Anthonisz does the average of the boxing values calculated by Archimède and refind

355/113=3.14159292... In any case it's what his son claims by

publishing the result in 1625. Those values where hold to be exact for  . Since the

greeks, we knew that there exist some numbers more complicated than the

rationals (irrationals) like

. Since the

greeks, we knew that there exist some numbers more complicated than the

rationals (irrationals) like  . We felt that

. We felt that  was of more

complex nature, but we still tried to express it as a function of

simpler numbers. During that time, the decimal numeratation quickly

progress the decimal race that became a common sport and the records

did not leave the west...

was of more

complex nature, but we still tried to express it as a function of

simpler numbers. During that time, the decimal numeratation quickly

progress the decimal race that became a common sport and the records

did not leave the west...

Pushing the calculation further than Archimedes, the record in this area belong to

Ludolph Van Ceulen

(1539-1610), who found 20 decimales in 1596 with the help of a polygon

with  million sides, then 32 decimals with the help of a

polygon of

million sides, then 32 decimals with the help of a

polygon of  sides in a postum plublication in 1615, so to finally be

attributed and marked on his tombstone 35 decimals in 1621. What an

obsession ! Might as well say he spend his life to this excersice, and

for reward that

sides in a postum plublication in 1615, so to finally be

attributed and marked on his tombstone 35 decimals in 1621. What an

obsession ! Might as well say he spend his life to this excersice, and

for reward that  is called von Ceulen's number in Germany

!

is called von Ceulen's number in Germany

!

|

|

|

| Ludolph Van-Ceulen (1540-1610) |

|

|

| |

In fact there was not much real progress in

this period essentially due to the exclusie use of geometric approach,

which started to find its limit in the calculation of the decimals of  .

.

The squaring of the circle continued, but

started to give true problems... Leaving the geometric era which did

not give any solution, analysis will start looking at it, and we will

see, with success. Note that the Académie

des Sciences in France, had promise a reward for the solution, received

at this period several wrong errors. As "Le petit Archimède",

the best price in this domain is to someone named Liger which start to

prove that  , the rest follows...

, the rest follows...

2 Ah finally some analysis! (18th century - end 19th century)

The great turn happens with the manipulation more and more current of infinite sum and product in the mathematic world at the end of the midle ages.

2.1 The time of arguments

During this perid, some violent arguments

appeared: one of the most famous of them concern Leibniz

(1646-1716) and Newton (1642-1727) who

fighted over the parentship of of the discovery of diferential calculus

and loose a lot of energy.... There are still some who are skeptical

(Rolle, for example, who did not believe in this revolution and will

get angry at Varignon, but still give us one of the most famous thoerem

of this theory), differential calculus will change mathematics

forever... The reults apear rapidly and the research on  will largely

benifit from it. It's the first time that formulae does not translate

directly the link between the geometry from which we define

will largely

benifit from it. It's the first time that formulae does not translate

directly the link between the geometry from which we define  and

and  itself. It's in

fact one of the things that in my view is most fascinating in the study

of

itself. It's in

fact one of the things that in my view is most fascinating in the study

of  . We are

dealling with big formulae in which it is very difficult to recognise a

geometric property, and yet we find

. We are

dealling with big formulae in which it is very difficult to recognise a

geometric property, and yet we find  . And the price on the research of a solution

concerning the famous squaring the circle problem offered by the

académie des Sciences always gave a big interest on the

geometry. But all of this was not build in one day

:

. And the price on the research of a solution

concerning the famous squaring the circle problem offered by the

académie des Sciences always gave a big interest on the

geometry. But all of this was not build in one day

:

2.2 The premices of analysis

If there was a mathematician who symbolise a bit this passage of geometry to infinitesimal or the concious of infinity, its Wallis (1616-1703).

|

|

|

|

|

| Wallis (1616-1703) | Lord Brouncker (1620-1684) |

|

|

|

| |

His manipulation of infinite series and his

research on the area of a quarter of a circle (starting from the

integral  to reach

to reach  ) pushed him towards horizons yet unknow.

After a proof that stayed famous due to its twist and turns, he find a

very nice formula, the first infinite product of rationals converging

to Pi :

) pushed him towards horizons yet unknow.

After a proof that stayed famous due to its twist and turns, he find a

very nice formula, the first infinite product of rationals converging

to Pi :

|

(6) |

The convergence is very slow, but it is maybe

the first true serie converging to  coming from analysis. Succeding it is Lord

Brouncker (1620-1684), a friend of Wallis,

who, upon being asked, continue the research on continued fractions and

change Wallis result into a famous

developpment of

coming from analysis. Succeding it is Lord

Brouncker (1620-1684), a friend of Wallis,

who, upon being asked, continue the research on continued fractions and

change Wallis result into a famous

developpment of  which gives:

which gives:

|

(7) |

All of this is centered on infinitesimal but its only with differential calculus that techniques will start to flower.

2.3 The first series

Well before the european, we attributes to

the Indians the first expression of  under serie forms since we find in the

writtings of the disciples of Nilakantha Somayaji (1444 - 1545 !) the

formula

under serie forms since we find in the

writtings of the disciples of Nilakantha Somayaji (1444 - 1545 !) the

formula

|

(8) |

among eight other. Its simplicity and the speed

of convergence (roughly  correct decimals for

correct decimals for  terms) could have lead mathematicians of that era to know some tens of

decimals of

terms) could have lead mathematicians of that era to know some tens of

decimals of  ! However, during this time, as we have seen above, its Al Kashi of Samarkande who did an amazing

feat by calculating 14 decimals of

! However, during this time, as we have seen above, its Al Kashi of Samarkande who did an amazing

feat by calculating 14 decimals of  in 1429 with the help of a variant on Archimede's method and in sexagesimal system.

in 1429 with the help of a variant on Archimede's method and in sexagesimal system.

In Europe, it's war! Newton

and his battles against Leibniz and

his  ...

One like the other have at least the merit of habing the vision of

great changes in mathematics. The application of differential calculus

finally allows to obtain or justify the limits of infinite serie as

usual functions (through for example the famous Taylor's formula).

During that time, James Gregory (1638-1675) make Europe benifit from

his discovery of the development in integer series of the arctan

function

...

One like the other have at least the merit of habing the vision of

great changes in mathematics. The application of differential calculus

finally allows to obtain or justify the limits of infinite serie as

usual functions (through for example the famous Taylor's formula).

During that time, James Gregory (1638-1675) make Europe benifit from

his discovery of the development in integer series of the arctan

function

|

(9) |

Applying  immediatly give a seire for Pi, but,

funnily enough,

Gregory missed it (or more probably, did not see the point in it) and

it only finds itself in the work by Leibniz.

In 1671, it's Abraham Sharp (1651-1742) which use the particular case

immediatly give a seire for Pi, but,

funnily enough,

Gregory missed it (or more probably, did not see the point in it) and

it only finds itself in the work by Leibniz.

In 1671, it's Abraham Sharp (1651-1742) which use the particular case  ,

in other words the equation 8,

so to obtain 71 correct decimals of

,

in other words the equation 8,

so to obtain 71 correct decimals of  in 1699,

nearly 200 years after Nilakantha ! The development of arcsin was

obtained by Newton towards

1665-1666, who took advantage to calculate 15 decimals of

in 1699,

nearly 200 years after Nilakantha ! The development of arcsin was

obtained by Newton towards

1665-1666, who took advantage to calculate 15 decimals of  , having

"nothing better to do" as he said it himself.

, having

"nothing better to do" as he said it himself.

|

|

|

| Newton (1642-1727) |

|

|

| |

The function arctan is a good candidate for

the calculation of the decimals of  by hand because if we take it from the right

side, we use only rational terms or at worst with a root like in 8. Hence John Machin (1680-1752) easily reaches 100

decimals in 1706 by proposing the now famous formulae

by hand because if we take it from the right

side, we use only rational terms or at worst with a root like in 8. Hence John Machin (1680-1752) easily reaches 100

decimals in 1706 by proposing the now famous formulae

|

(10) |

|

|

|

| John Machin (1680-1752) |

|

|

| |

The proof or the research of this kind of formulae (from which four other examples are given further by the equation 12, 13, 23 and 24) are obtained by the following rule

Theorem 2.1 Let

and

and  be integers.

be integers.  ,

,  , if and only if

, if and only if  .

.

Proof. If  ,

, ![( prod p ) sum p

ln j=1 (aj + i.bj) = j=1 [ln(| cj|)+ i.(arg(cj)+ 2kjp)]](../histoire/histoire110x.gif)

![sum p [ ( (bj) )]

= j=1 ln(|cj|)+ i. arctan aj + 2kjp](../histoire/histoire111x.gif) ,

,  . Consequently

. Consequently  iff

iff  such that

such that  , iff

, iff  such

that

such

that  . __

. __

The speed of convergence of these formulae is

constrained by the greatest term  and according to equation 9, we obtain a

linear convergence, in other word a number

and according to equation 9, we obtain a

linear convergence, in other word a number  of decimals

by using

of decimals

by using  terms of Taylor's expansion of the funtion

terms of Taylor's expansion of the funtion  . From now

on, the combination of arctan will be used as a basis for the race to

decimals until 1985 !

. From now

on, the combination of arctan will be used as a basis for the race to

decimals until 1985 !

2.4 The lord of the series

After that the mathematics predominance was installed in England under the impulsion of Newton, they come back to the old continent, in Swiss notably with the Bernoulli and Euler. Its the great analysis period. Euler searches everywhere and never tires of publishing to gives use numerous formulae. The most beautiful of them is with no doubt :

which brings not much to the calculation of decimals but whose simplicity is remarquable... It's proof (see Euler page) is a one of a kind, completly not rigourous, but completly amazing!

|

|

|

| Euler (1707-1783) |

|

|

| |

A century late, a mathematician which

according to me will indirectly bring the most to the research on  is

Joseph Fourier (1768-1830). His theory

on the decomposition of periodic functions into series, still to be

finalised but who will be the object of rigourousity thorughtout the

19th century, and which is truly revolutionary (so much that certain

mathematicians of the period like Poisson will try to fight back with

loads of energy!). The result allows in fact to simply reprove about

nearly all those formulae of our good old friend Euler.

And of course find new quite interesting ones.

is

Joseph Fourier (1768-1830). His theory

on the decomposition of periodic functions into series, still to be

finalised but who will be the object of rigourousity thorughtout the

19th century, and which is truly revolutionary (so much that certain

mathematicians of the period like Poisson will try to fight back with

loads of energy!). The result allows in fact to simply reprove about

nearly all those formulae of our good old friend Euler.

And of course find new quite interesting ones.

2.5  , probably...

, probably...

, it's not only geometry and analysis ! Buffon (1707-1788) prove to us with his

famous needle problem that

, it's not only geometry and analysis ! Buffon (1707-1788) prove to us with his

famous needle problem that  also intervened in the domain of probability.

Of course, this is still due to the definition of

also intervened in the domain of probability.

Of course, this is still due to the definition of  as the

component of the area and the perimeter of a circle, but the theorem by

Cesàro (1859

- 1906) will confirm the inclusion of

as the

component of the area and the perimeter of a circle, but the theorem by

Cesàro (1859

- 1906) will confirm the inclusion of  in the

probabilities...

in the

probabilities...

|

|

|

|

|

| Buffon (1707-1788) | Cesàro (1859-1906) |

|

|

|

| |

2.6 The challenge

Let us go back to our chronicle race.

Starting from Newton, they are - without

insulting them - more second hand mathematicians who fight for the

record of decimals. Anyway, the number of decimal already calculated in

those time was greater than the needs of mathematicians or physicians.

In fact we estimate that to calculate the circumference of the universe

with the precision of a hydrogen atom, only 39 decimals of  are required !

The motivations are hence more turned towards the search of periodicity

or patterns in the decimals of

are required !

The motivations are hence more turned towards the search of periodicity

or patterns in the decimals of  .

The periodicity of a number makes it rational (numbers written as a

fraction

.

The periodicity of a number makes it rational (numbers written as a

fraction  ,

,

,

,  integers).

However, at the turn of the 18th and 19th century, the problem of the

irrationality of

integers).

However, at the turn of the 18th and 19th century, the problem of the

irrationality of  , in other words the impossibility to write it under

rational form, still bother mathematicians. They suspect its true

for a long time but never managed to prove it. With the progress of

analysis, Euler show the irrationality

of

, in other words the impossibility to write it under

rational form, still bother mathematicians. They suspect its true

for a long time but never managed to prove it. With the progress of

analysis, Euler show the irrationality

of  and

Johann Lambert (1728-1777) brings an

answer to the problem of

and

Johann Lambert (1728-1777) brings an

answer to the problem of  in 1761. His rather heavy proof uses a expansion in

continued fraction of the function

in 1761. His rather heavy proof uses a expansion in

continued fraction of the function  .

Pi is truly irrational

!

.

Pi is truly irrational

!

|

|

|

| Lambert (1728-1777) |

|

|

| |

In truth the maybe paradoxly more important result that we have found on the spread of the decimals of Pi such that this last remains a mystery to us today. The irrationality indicates that they are not periodic...

There's still the isue of transcendental, in

other words the impossibility to represent  as a

combination of roots and powers of integers, or in equivalent terms,

the fact that

as a

combination of roots and powers of integers, or in equivalent terms,

the fact that  is not the root of any polynomials with integer

coefficients, or even the impossibility of squaring a circle. Even with

all the efforts of many mathematicians (and amateurs that are still

trying to solve the squaring of the circle!), this fort stayed

unbreachable until the end of the 19th century. And the crazy entries

by amateur mathematicians obliged the académie des Sciences to

refuse starting from 1775 the tentavives of proofs on the squaring the

circle , immediate consequence of the transcendance.

is not the root of any polynomials with integer

coefficients, or even the impossibility of squaring a circle. Even with

all the efforts of many mathematicians (and amateurs that are still

trying to solve the squaring of the circle!), this fort stayed

unbreachable until the end of the 19th century. And the crazy entries

by amateur mathematicians obliged the académie des Sciences to

refuse starting from 1775 the tentavives of proofs on the squaring the

circle , immediate consequence of the transcendance.

2.7  falls in the

shadow

falls in the

shadow

The 19th century comes by... Bizarely,

the most brilliant representant of the scientific genius of the

century, Master Gauss

(1777-1855), even with his uncomparable talent, was not one interested

at all by the research on  , at least not direcly. We do need to credit

him with a few arctan formulae, but nothing to worship him by !

, at least not direcly. We do need to credit

him with a few arctan formulae, but nothing to worship him by !

Even if Pi continues to appears in many

results, the 19th century is more directed towards algebra and

arithmetics with Galois, Abel, Sophie

Germain and the new theoricians of the non euclidian geometry such as Gauss, Beltrami,

Lobatchevski and Bolyai. The calculation of decimals seems to run out

of breath in the second half of the 19th century. All of this even with

the extraordinary talent of Zacharias Dase, and the enthousiams of a

few like Shanks. Employed by Strassnitsky to calculate 200

decimals, which he did in two month, Dase was the announcer of modern

computers with his fantastic capacity to calculate (he could multiply

in his head two numbers of 100 digits in 8hrs, with breaks, or even

sleeping on it for a whole night, and starting again later!). It needs

to be mentioned that the calculation of decimals by hand seems to have

reach humain limits in 1874 with 707 decimals calculated by Shanks,

which are in fact false starting from the  .

Ferguson will notice it nearly 70 years later when comparing them to

the

.

Ferguson will notice it nearly 70 years later when comparing them to

the  that he obtained in 1948, with the first calculating machines

(addtioners in fact, herited from the principle of those constructed by

Leibniz since 1694). An error that will have hence lasted 92 years

! The room of the palais de la découverte in Paris which proudly

showed off the result by

Shanks decided it was a good idea to be refurnished

!

that he obtained in 1948, with the first calculating machines

(addtioners in fact, herited from the principle of those constructed by

Leibniz since 1694). An error that will have hence lasted 92 years

! The room of the palais de la découverte in Paris which proudly

showed off the result by

Shanks decided it was a good idea to be refurnished

!

|

|

|

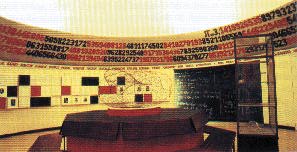

| The room consacred to maths in the Palais de la Découverte in Paris. |

|

|

| |

And since the arctan formulae, we have still have not find in that era a way to go faster and further in the thoery like in practise...

Furthermore, the oldest mathematical problems

was found to be solved in Lindemann in

1882 when he proved the transcendance of  . The squaring

of the circle is hence impossible... How are we going to exist this

impass and remotivate ourself ?

. The squaring

of the circle is hence impossible... How are we going to exist this

impass and remotivate ourself ?

It's from the depth of India at the end of the 19th century that someone grows and will remodel and reshape the century to come.... The era of algorithm and computing will start with him....

3 Computers take the relay

3.1 The Indian breath

During the first half of the 20th century, the mathematicians preoccupation were elsewhere. The theories elaborate by Cantor, Gödel, Kolmogorov, the topologie and the list of 23 problems by Hilbert opens sundunly the horizon which made classical analysis look ancient. It seemed to have found its natural evolution in the study of elliptical integral lead by Legendre, then Gauss, Abel and Jacobi during the first half of the 19th century.

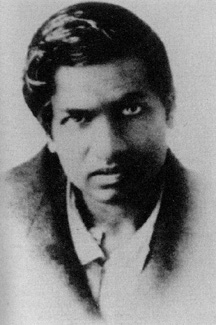

Luckuly a genius born in the depth of India in

1887, Srinivasa Ramanujan , will bring it on himself to

bring new life to research on  .

.

|

|

|

| Srinivasa Ramanujan (1887 - 1920). |

|

|

| |

Himself passionated by this constant, he's a self taught man who spend his first 25 years of his life rebuilding the mathematics from a unique work containing 6165 theorems without proofs ("Synopsis of elementary results in pure and applied mathematics” by G.S.Carr). This state of mind lead him to often state results without proving them (which did not mean he did not understand where they came from!). Gifted with exceptional intuition allowed to progress with giant leapsteps in the tehory numbers and modular equation, he discovered some formulae from an other angles like this one published in 1914

|

(11) |

There exists a funny story about this formula: his proof was nearly completed at the start of the 80s by the Borwein's brothers [7].

|

|

|

|

|

|

Borwein Brothers

|

|

|

|

|

| |

|

They just had to justified the 1103

coefficient, it should be an integer, but the length of the calculation

and equations required were horible. Gosper

then effected in 1895 a "blind" calculation of 17 million decimals of  with the help

of this formula. As true as two integer close of less than a unit are

equal, the concordance of the result of the calculation by Gosper with the 10 millions of

decimals already knew at that time constituted of a final proof for the

formula Ramanujan ! We suppose that Ramanujan did the same procedure on a

few decimals.

with the help

of this formula. As true as two integer close of less than a unit are

equal, the concordance of the result of the calculation by Gosper with the 10 millions of

decimals already knew at that time constituted of a final proof for the

formula Ramanujan ! We suppose that Ramanujan did the same procedure on a

few decimals.

The Borwein

will get from the work of Ramanujan

a flow of remarquable algorithm still largely used today in the

calculations of the decimals of  (see paragraph 3.5).

The complexity of the proof of such a formula is such that even a

glance at the results, with no interdemiate proofs, take up a minimum

of several pages in the remarquable work[13]. The reader interested to take a dive

in the passionating world of modular equation, quartic bodies, and

other elliptical integrals can refer themself to the "Bible" [7], of great pedagogie.

(see paragraph 3.5).

The complexity of the proof of such a formula is such that even a

glance at the results, with no interdemiate proofs, take up a minimum

of several pages in the remarquable work[13]. The reader interested to take a dive

in the passionating world of modular equation, quartic bodies, and

other elliptical integrals can refer themself to the "Bible" [7], of great pedagogie.

Ramanujan was noticed by the English mathematician Hardy to which he wrote a letter to in 1913, went to England in 1914 and their fruitful collaboration lasted until 1919.

|

|

|

| Hardy (1877-1947) |

|

|

| |

He then went back to India were he died the following year, probably due to a lack of victamin. Considered as one of the greatest genius of the 20th cebtury, Ramanujan left notebooks full with loads of formulae in non-standards notations, whose decoding is still hapening today (!), first started by Bruce Berndt, then the Borwein.

3.2 The race to the decimals start again

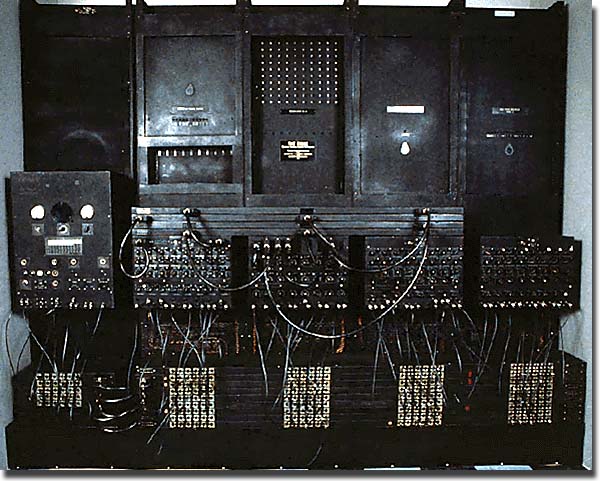

After Ramanujan who died prematuratly in 1920, its a theoretical desert... until 1976. Hence, during this time, we calculate... After the war, the dawn of calculating machine make the race of decimals progress with giants leaps! Ferguson opens the way in 1946 by obtaining 620 decimals with the help of a desk calculator. The first calculation on computers was given to the famous ENIAC in 1949 which gives 2037 decimals in 70 hours with the help by the formula by Machin 10.

|

|

|

| ENIAC |

|

|

| |

In 1973, Guilloud and Bouyer reached the first

million decimals on a CDC 7600 with the help of two famous  formulae,

the one by Gauss 12

and of

Störmer 13

formulae,

the one by Gauss 12

and of

Störmer 13

|

(12) |

|

(13) |

The calculation in binary took respectivaly 22hr11 and 13hr40, and the conversion in decimal base 1h07. A book of 145 pages of decimals pulled from this calculation was qualified at the time as the "most boring book in the world"!

Note that process attach to the race of

decimals is still the same as today: the calculations are fone with two

distinc formulae then compared for the validation of the record. The

figures 1

and 2

shows the evolution of the records of the calculation of the decimals

of  throughout the centuries.

throughout the centuries.

|

3.3 Improvements in algorithms

During this time, the lack of efficient

multiplication algorithm forced to break down each numbers into slices,

for example  . The multiplication of

numbers of size

. The multiplication of

numbers of size  hence needed a time (or number of operations)

proportional to

hence needed a time (or number of operations)

proportional to  without taking into account the use of memory

proportional to

without taking into account the use of memory

proportional to  . With no theoretical and algorithmical improvement, the

progress of records of decimals would have been very slow. It was at

this time that things sped up.

. With no theoretical and algorithmical improvement, the

progress of records of decimals would have been very slow. It was at

this time that things sped up.

In 1965, Cooley et

Tukey introduced under it's modern form a method to reduce the

complexity of the calculation of Fourier

series known today under the name of Fast Fourier Transformation [11]. Schönhage and

Strassen get from it an multiplication algorithm for big integers in

complexity  which is much better

than

which is much better

than  [24]

!

[24]

!

In 1976, Salamin and Brent managed independently to the same algorithm ([23, 8])

which has the extraordinary property of a

quadratic convergence, in other words the number of exact decimals

doubles at each iteration. In fact, Salamin

shows in [23] that

if  is

the approximation of

is

the approximation of  after

after  iteration of the algorithm 14,

we get

iteration of the algorithm 14,

we get

|

(16) |

This upper limits shows that the number of

correct decimals of  obtained from is stricly greater than

obtained from is stricly greater than  .

.  is the arithmetic geometric average (see the page on Salamin).

is the arithmetic geometric average (see the page on Salamin).

|

|

|

| Richard Brent |

|

|

| |

Let us finaly add that the algorithm by Newton, offered towards 1669 (!), brings back the division and the extraction of square roots to multiplications and also offer a quadratic convergence. Might as well say that all the ingrediants are brought together to make the records explodes !

3.4 World competition

In fact the competition restart in 1981 with

Kanada's team which was probably the first to apply this cocktail of

algorithms (FFT , Newton, Brent-Salamin).

Myioshi and Kanada obtained 2 000 036

decimals in 1981. Strating from this moment, the rythm speeds up, since

the poor Guilloud, which tried to keep his record in 1982 by

calculating 14 decimals more than the Japanese couple, find himself out

of the competition at the end of 1982, when we know 16 777 206 decimals

(Kanada, Yochino and Tamura). The fight then will mainly concern Kanada

and, between 1991 and 1994, the two brothers David and Gregory Chudnovsky which use their own serie

of kind Ramanujan and a computer who

they themself construct the architecture. According to the legend,

their New-York flat contained piles of papers in disorder and was

heated with microchips ! Those isolated mathematicians but with

recognised talent (Gregory is considered as an exceptional genius but

an illness stops him from working at a uni) shows at least that some

first class scientist are interested in the calculation of the decimals

of  [12].

[12].

3.5 A rainfall of formulae

The 80s see the birth of several very

interesting formulae concerning  . There was some formulae of kind Ramanujan, some infinite series converging

linearly but fast enough that they are used in the records. These are

refound and explained thanks to the decyphering of the Ramanujan's notebook by Bruce Berndt and the

work of the Borwein

brother and Chudnovsky.

. There was some formulae of kind Ramanujan, some infinite series converging

linearly but fast enough that they are used in the records. These are

refound and explained thanks to the decyphering of the Ramanujan's notebook by Bruce Berndt and the

work of the Borwein

brother and Chudnovsky.

In other part, starting from modular equations implied that the theta functions (whose algorithm by Brent-Salamin was a particular case), the Borwein brothers showed that we can construct algorithms that converges to any speed (quadratic, quartic, quintic...) towards Pi even if the complexity of the calculations increases as a consequence. A good compromise seemed to be the following formula, with quartic convergence [7] :

It was used for the first time by Bailey then Kanada in 1986. Bailey used 12 iterations on a CRAY-2 to calculate 29 360 000

decimals of  (in fact 45 millions are possible at that stage). It is ammusing to

notice that there only need 100 multiplication, division and extraction

of roots to reach it !

(in fact 45 millions are possible at that stage). It is ammusing to

notice that there only need 100 multiplication, division and extraction

of roots to reach it !

From 1982 to 2002, it is still formulae by Ramanujan (like 11),

the algorithm by Brent-Salamin (14) or a

variant, as well the quartic algorithm of Borwein

(17) which were

used in the race of the calculation of decimals of  . The first

billion were obtained by the Chudnovsky

brothers in 1989 and, with this method, Kanada, always him, reached

206 billion decimals of

. The first

billion were obtained by the Chudnovsky

brothers in 1989 and, with this method, Kanada, always him, reached

206 billion decimals of  in 1999. Of course, Pi having an infinite number of

decimals, it's not even a drop of water, but the mathematicians hoped

still find, like the Chudnovsky brothers,

some irregularity or property in the decimals of our favourite

constant...

in 1999. Of course, Pi having an infinite number of

decimals, it's not even a drop of water, but the mathematicians hoped

still find, like the Chudnovsky brothers,

some irregularity or property in the decimals of our favourite

constant...

|

|

|

| Chudnovsky Brothers |

|

|

| |

|

|

|

From left to right, Salamin,

Kanada, Bailey and Gosper in 87. Ah, the crazy night betweens friends

on  ! ! |

|

|

| |

4 BBP

approche, more new stuff on

4.1 How to progress ?

The multiplication, the division and

extraction of roots now can be done in a nealry linear time, and

knowing that we can not have less than a complexity  , we can not

expect much more significant advance from this angle. We have seen that

some extremly efficient algorithms existed for the calculation of the

decimals of

, we can not

expect much more significant advance from this angle. We have seen that

some extremly efficient algorithms existed for the calculation of the

decimals of  .

Are we then doomed to see the record fall in function to the

progression of computer performances? Yes and no!

.

Are we then doomed to see the record fall in function to the

progression of computer performances? Yes and no!

The mathematicians often surprises where we least expect it. This is how on the 19th september 1995 at 0hr29 (!), after months of research in the dark, Simon Plouffe, David Bailey and Peter Borwein of Vancouver discovered the formula apparently normal and simple

|

(18) |

called since then the BBP formula. The proof is

nearly immediate if we notice that  then by calculating the equivalent integral to 18. Euler himself could have discovered it. In

fact, it is to this day one of the most famous example of experimental

maths since this formula was discovered by the algorithm PSLQ of

research on linear relation between numbers. This encouraged the number

of amateurs in mathematicians to start the research of such formulae

thanks to PSLQ or LLL, a similar algorithm implemented on the Pari-GP software.

then by calculating the equivalent integral to 18. Euler himself could have discovered it. In

fact, it is to this day one of the most famous example of experimental

maths since this formula was discovered by the algorithm PSLQ of

research on linear relation between numbers. This encouraged the number

of amateurs in mathematicians to start the research of such formulae

thanks to PSLQ or LLL, a similar algorithm implemented on the Pari-GP software.

|

|

|

| Simon Plouffe |

|

|

| |

But our three canadian mathematician noticed

above all that this expression is very close to a decomposition in base

16 of  . In

the article [3] of 1996

that is now famous, they show that we can use 18

to reach

. In

the article [3] of 1996

that is now famous, they show that we can use 18

to reach  -th

digit of

-th

digit of  in base

in base  (all the more in base 16) without calculating any of the previous, all

of this in a nearly linear time

(all the more in base 16) without calculating any of the previous, all

of this in a nearly linear time  ) and memory

) and memory  !! The

memory required being minimal, they applied immediatly this result to

calculate the

!! The

memory required being minimal, they applied immediatly this result to

calculate the  bilionth digit of

bilionth digit of  in base 2. The revolution had started.

in base 2. The revolution had started.

Plouffe

extend this result in all the bases  in octobre

1996 [22] to the

price of a time

in octobre

1996 [22] to the

price of a time  and the clever uses of the serie

and the clever uses of the serie

|

(19) |

Some improvement in  then

in

then

in  are

successively offered by Bellard in

1997 [5] then

Gourdon in 2003 [14].

Numerous other formulae of type BBP ( with powers of

are

successively offered by Bellard in

1997 [5] then

Gourdon in 2003 [14].

Numerous other formulae of type BBP ( with powers of  or

or  ) have since

then seen the day for the logarithm of integers,

) have since

then seen the day for the logarithm of integers,  ,

,  , the

Catalan's constant

, the

Catalan's constant  , and in general polylogarithm constants [9, 17].

Unfortunatly, there propably does not exist any formula for

, and in general polylogarithm constants [9, 17].

Unfortunatly, there propably does not exist any formula for  with a power

with a power  , in other

words in base

, in other

words in base  . The formula

. The formula  shows however we can calculate isolated decimal digits of certain

constants.

shows however we can calculate isolated decimal digits of certain

constants.

Those fundamental results shows in particular

that  belongs to the class of complexity of Steven

belongs to the class of complexity of Steven  ,

regrouping the constants that we can calculate the digits in base

,

regrouping the constants that we can calculate the digits in base  in polynomial

time and memory

in polynomial

time and memory  -polynomial, which was before judged to be improbable

from a memory point of view.

-polynomial, which was before judged to be improbable

from a memory point of view.

Since then, Fabrice Bellard,

a Polytechnician French studient, managed to reach the 1000 billionth

digit in septembre 1997. Then Colin Percival reached the  -th

binart digit of

-th

binart digit of  (a

(a  !) by a collaboratif calculation on the internet of 1.2

million hours of shared CPU between 1734 computers spread in 56

countries between the 5th septembre 1998 and the 11th september 2000!

!) by a collaboratif calculation on the internet of 1.2

million hours of shared CPU between 1734 computers spread in 56

countries between the 5th septembre 1998 and the 11th september 2000!

The principle of this calculation of the  -th digit of

-th digit of  is given on

the page N-th

digit.

is given on

the page N-th

digit.

4.2 A formula full of resources

The nearly direct access of the digits of

those constants seeded the idea in mathematicians that we can find some

properties on the spread of those digits , and that we can be near a

proof for the normality of  (and hence the irrationality of the Catalan's

constant

(and hence the irrationality of the Catalan's

constant  or the odd

or the odd  ). The normality of a number requires that each

). The normality of a number requires that each  -uplet possible

appears with a probability

-uplet possible

appears with a probability  in the digits in base

in the digits in base  of this

number. For example each digits between

of this

number. For example each digits between  and

and  appear on

average once on

appear on

average once on  , each number between

, each number between  and

and  appears once

on

appears once

on  , and

so on. In octobre 2000, Bailey and

Crandall reduced this condition on normality to the satisfaction on the

following hypothesis

:

, and

so on. In octobre 2000, Bailey and

Crandall reduced this condition on normality to the satisfaction on the

following hypothesis

:

Conjecture 4.1 Let

,

,  , with

, with  and

and  without poles on

without poles on  (its the polynomial

part of the BBP formulae). Let a base

(its the polynomial

part of the BBP formulae). Let a base  and

and  . The the sequence

. The the sequence

defined

by

defined

by

|

(20) |

has a finite attractor

or is equally spread on ![[0,1]](../histoire/histoire235x.gif) .

.

|

|

|

| Richard E. Crandall |

|

|

| |

This kind of sequence is equivalent to the BBP

representation of a constant since if  , then

, then  where

where  tends to 0

if

tends to 0

if  since

since  .

.

The condition of a finite attractor represent intuitively the fact that for a sequence of always approaching a set of finite value starting from a certain rang, and in any order, as we are tending it towards a genral rational (whose decimal sequence are periodic.

Definition 4.2 Precisly,

a sequence

![(xn)n (- N (- [0,1]](../histoire/histoire241x.gif) has a finite attractor

has a finite attractor  if

there exist

if

there exist  and such that for all

and such that for all  ,

,

|

(21) |

We can furthermore show that in our case (BBP

formulae), this property is equivalent to the rationality of the limit

of  [4]. The notion of

evenly spreaded is more intuitive. It is checked if the proportion of

the appearation of a sequence of values in

[4]. The notion of

evenly spreaded is more intuitive. It is checked if the proportion of

the appearation of a sequence of values in ![[0,1]](../histoire/histoire248x.gif) in a given

interval

in a given

interval ![[c,d]](../histoire/histoire249x.gif) is exactly the length of that interval, basicly the

values taken are uniformly spread in

is exactly the length of that interval, basicly the

values taken are uniformly spread in ![[0,1]](../histoire/histoire250x.gif) .

.  is

evenly spread if

is

evenly spread if

![lim Card-{xj (- -[c,d], j-<-n} = d- c.

n--> oo n](../histoire/histoire252x.gif) |

(22) |

The evenly spread for this kind of sequence

implies the normality [19].

Taking into account the various implied constants in the BBP

representation, we scratch here some important improvement, especially

for the odd  . It is amusing to see the simplicity of the BBP formula that leads to

all those consequences. Consult [4, 20]

to expand on those open questions.

. It is amusing to see the simplicity of the BBP formula that leads to

all those consequences. Consult [4, 20]

to expand on those open questions.

5 An endless quest ?

5.1 Record to date

The 6th december 2002. Kanada, untirable

competitor who holds or reclaim the record in the calculation of the

decimals of  for more than 20 years, calculated 1 241 100 000 000 decimals of

for more than 20 years, calculated 1 241 100 000 000 decimals of  . The surprise

came from the fact that this time he only used two formula of the type Machin like equation 10.

. The surprise

came from the fact that this time he only used two formula of the type Machin like equation 10.

This comeback to suprisingly simple formulae after the use for fifteen years algorithms of Brent-Salamin, or Borwein or series of Ramanujan and Chudnovsky was really unexpected. It seems that the perpetual uses of roots, multiplications and divisions needed for the use of FFT was on a great scale. This last requires a lot of memory to function. Kanada hence went back to some wiser method like the formulae of type Machin, which sensibly needs more arithmetic operation but less FFT and hence a lot less memory. Kanada estimated that his implementation is roughly two time faster than the previous one he used, the algorithm 14 of Brent-Salamin and the one of quartic order by the Borwein (eq. 17). The calculations were done in hexadecimal base, i.e. 1 030 700 000 000 digits. The used formulae were :

The first was found in 1982 by a math profesor and composor, Takano, and the second was a discovery of Störmer in 1896.

This calculation by Kanada holds a second

suprise: since the result was obtained in base  , after

checking the equality between the two calculation, he then did a second

check by directly calculating the 20 hexadecimal digits at the position

1 000 000 000 001 with the help of BBP formulae presented previously.

The result B4466E8D21 5388C4E014, which required 21 hours of work,

perfectly corresponded to the calculation done with the help of

, after

checking the equality between the two calculation, he then did a second

check by directly calculating the 20 hexadecimal digits at the position

1 000 000 000 001 with the help of BBP formulae presented previously.

The result B4466E8D21 5388C4E014, which required 21 hours of work,

perfectly corresponded to the calculation done with the help of  formulae.

The hexadecimals digits were then converted in base ten, a not so

trivial operation, reconverted into hexadecimals for verification, then

the record was official [2].

formulae.

The hexadecimals digits were then converted in base ten, a not so

trivial operation, reconverted into hexadecimals for verification, then

the record was official [2].

The calculations (everything included) lasted around 600 hours on a HITACHI SR8000/MP with 1TB of memory (1024GB), i.e. the same amount of memory as for its previous record of 1999, even though 6 times more decimals were calculated!

5.2 Perspective and motivation

How to explain that the race to the decimals

is still current news? The motivation to beat the record of decimals of

have

in fact never run out. We will mention mixed and mash the test of

computer (a bug was discovered by Bailey

during his record of the calculation in 1986 on a Cray-2), the hypothesis of irregular

appearance in the spread of calculated decimals (still nothing on that

side) or the addition of yet more efficient implementation of the

decimal calculation (the computation is running like a fever on the

internet between several mathematician programer for the title of the

fastest program in the world).

have

in fact never run out. We will mention mixed and mash the test of

computer (a bug was discovered by Bailey

during his record of the calculation in 1986 on a Cray-2), the hypothesis of irregular

appearance in the spread of calculated decimals (still nothing on that

side) or the addition of yet more efficient implementation of the

decimal calculation (the computation is running like a fever on the

internet between several mathematician programer for the title of the

fastest program in the world).

Each of these reason taken seperatly is not

sufficient. It would be more truthful to say that its the conjection of

all those reason, without taking into account the passion started by

the "personality" of  , which feeds and renew the competition. It is tru that

the mordern implementation of arithmetic libraries on large numbers

(based on the FFT , and Newton technics seen previously)

helped a lot in the race of decimals of

, which feeds and renew the competition. It is tru that

the mordern implementation of arithmetic libraries on large numbers

(based on the FFT , and Newton technics seen previously)

helped a lot in the race of decimals of  . It is also

true that putting together efficient program is not in everyone's reach

and that you need to carefully know the architecture of your calculator

to have any hope of an interesting performance. It's a challange for

numerous computer scientist gifted in maths (or the other way round!).

We have also seen that the recent discovery of the BBP formula 18 opened up a

large field of theoretical investigation.

. It is also

true that putting together efficient program is not in everyone's reach

and that you need to carefully know the architecture of your calculator

to have any hope of an interesting performance. It's a challange for

numerous computer scientist gifted in maths (or the other way round!).

We have also seen that the recent discovery of the BBP formula 18 opened up a

large field of theoretical investigation.

I will add that the popalarity of  plays an

important role: it is this justification that is maybe rarely mentioned

but which is taken in full with simple amators of matheamticians member

of the lovers of

plays an

important role: it is this justification that is maybe rarely mentioned

but which is taken in full with simple amators of matheamticians member

of the lovers of  sects, or even visible by sifting through maths forums

over the worlds: the theory of numbers, classical analysis and the

constants have an accesible base, at least in appearance, for the

non-mathematicians and stay the greatest giver of little excersices of

some funny properties of numbers. Its through this bias that is born

many vocations of mathematics, and we just need to consult

mathematicians web pages like Bailey, Plouffe ,

Kanada or the Borwein brothers to be

convinced that they keep at over fifty years a refreshing passion for

the constants, visible part of the math iceberg. The difficulty of

abstraction of other mathematics domains like algebraic geometry

confines them more to a more knowledgeable audience and they do not

benifits from as many nearly universal symbols like

sects, or even visible by sifting through maths forums

over the worlds: the theory of numbers, classical analysis and the

constants have an accesible base, at least in appearance, for the

non-mathematicians and stay the greatest giver of little excersices of

some funny properties of numbers. Its through this bias that is born

many vocations of mathematics, and we just need to consult

mathematicians web pages like Bailey, Plouffe ,

Kanada or the Borwein brothers to be

convinced that they keep at over fifty years a refreshing passion for

the constants, visible part of the math iceberg. The difficulty of

abstraction of other mathematics domains like algebraic geometry

confines them more to a more knowledgeable audience and they do not